On November 12, 2025, the Chinese embassy in Tripoli officially reopened after more than a decade.[1] However, the return of Chinese diplomatic staff to the Libyan capital passed largely unnoticed, attracting scant media interest both domestically and abroad.[2] Most of the international coverage came from Italy,[3] where the news outlet Formiche[4] interviewed ChinaMed’s Head of Research Andrea Ghiselli on the matter.

According to Ghiselli, the reopening of the embassy in Tripoli may be linked to Beijing’s plans to restore its diplomatic mission in Syria later this year. Taken together, he argued, these moves suggest an effort by China to reintroduce a degree of “normalcy” into two long-standing Mediterranean dossiers. From this perspective, the unshuttering of the Chinese embassy in Tripoli may signal an attempt by Beijing to expand its diplomatic room for maneuver across the region.[5]

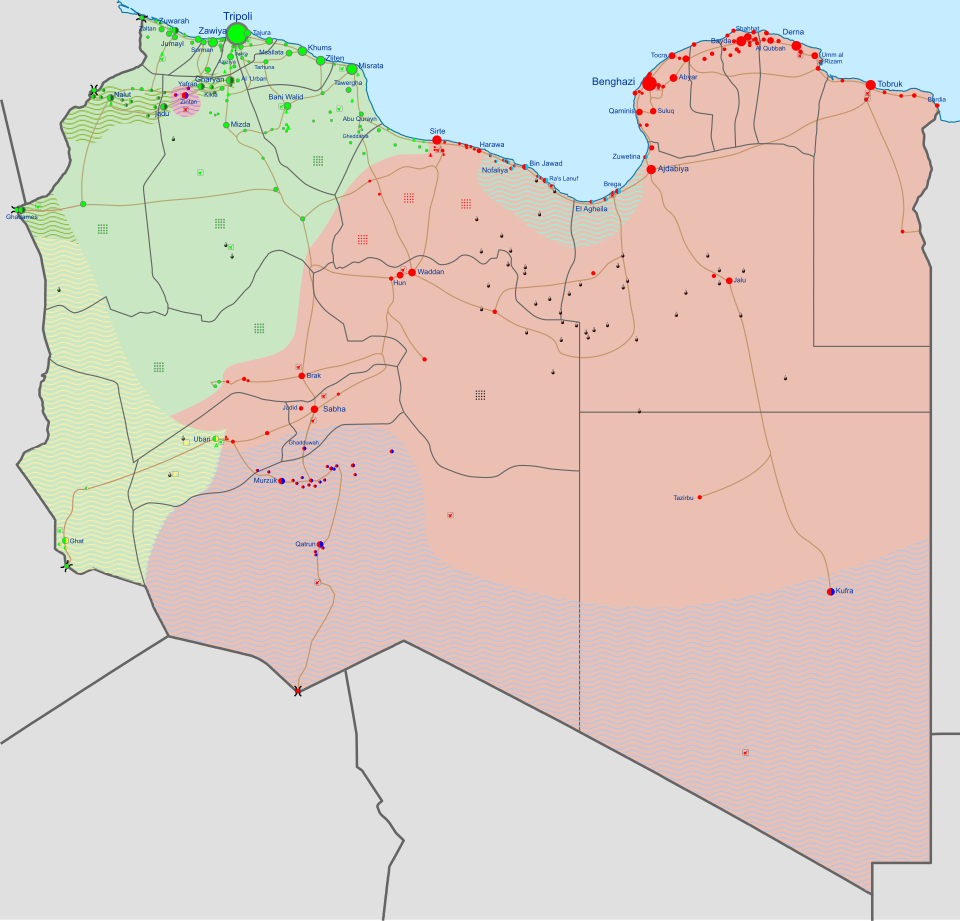

Ghiselli is careful, however, to draw a distinction. While Syria has succeeded in achieving a measure of territorial consolidation, international recognition and investment commitments under the leadership of Ahmed al-Sharaa, Libya, by contrast, remains deeply fragmented. The country is divided between the United Nations-recognized Government of National Unity (GNU) based in Tripoli in the west, and the de facto authority of military strongman Khalifa Haftar and his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) in the east.

Still, the Syrian comparison is useful. As in Syria, China’s role in Libya has often been overstated, swinging between inflated expectations and undue suspicion. This edition of the ChinaMed Observer therefore revisits the past decade of Chinese engagement in Libya, tracing Beijing’s evolving relations with the country’s factions and situating them within a regional context. We explore whether dynamics reminiscent of the end of the Syrian civil war are beginning to emerge in Libya, and whether such parallels can shed light on Beijing’s future approach to the Libyan crisis.

Our assessment aligns with Ghiselli’s argument: the reopening of the Chinese embassy signals normalization, but little beyond that. As the Syrian case shows, diplomatic engagement does not imply political commitment, let alone a readiness for direct involvement. China is thus unlikely to engage deeply in Libya’s power struggles. If anything, recent developments in Syria appear to be shaping Beijing’s approach to Libya, reinforcing a preference for caution, balance and neutrality. This posture is all the more likely given that Libya today is not only unresolved but far more crowded with external actors than Syria ever was. In such an environment, Beijing will likely opt to keep its options open – present, but uncommitted.

The Libyan crisis erupted in early 2011, when the Arab Spring swept in from neighboring Tunisia and Egypt, igniting mass protests against the long-entrenched rule of Muammar Gaddafi. What began as popular unrest quickly descended into a violent civil war, one that also upended foreign economic interests rooted in the country, notably those of China.

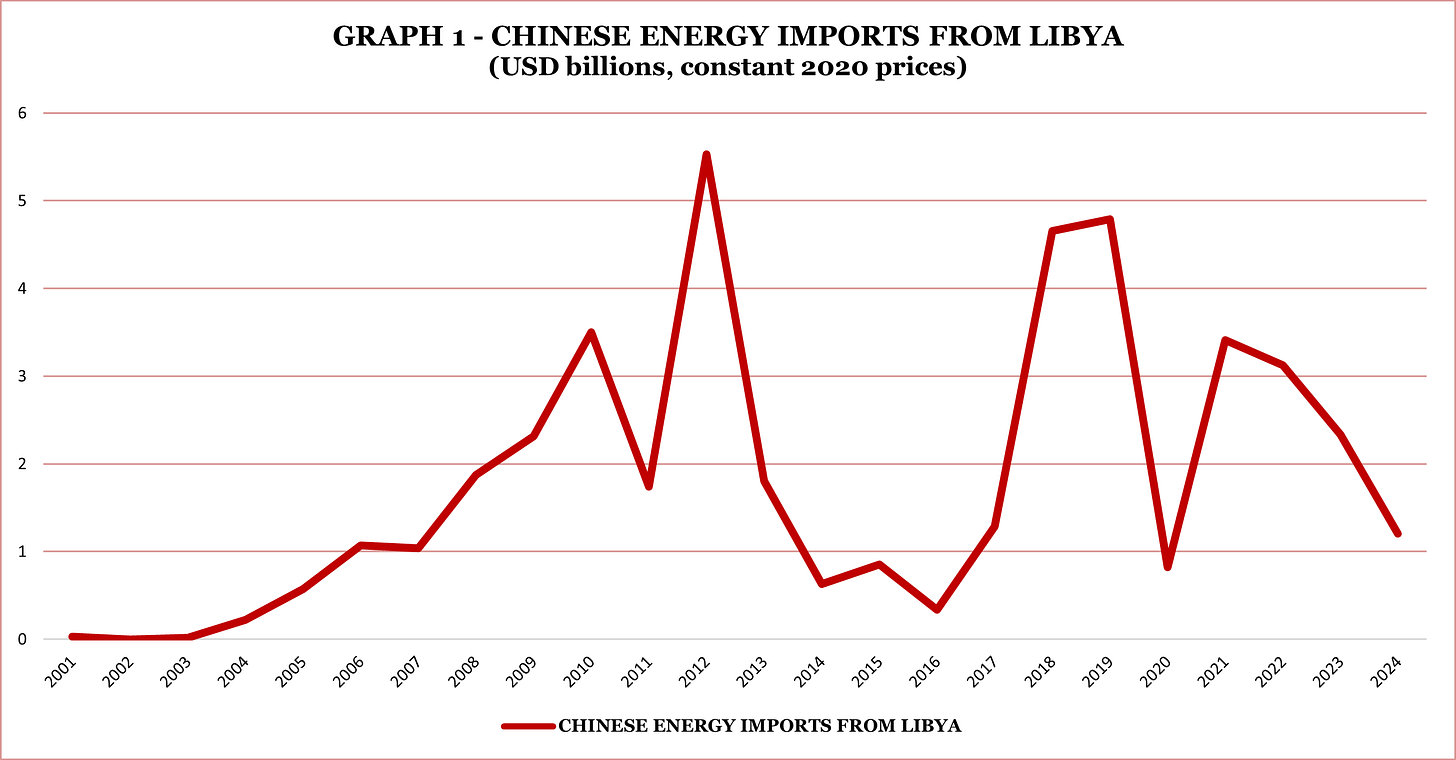

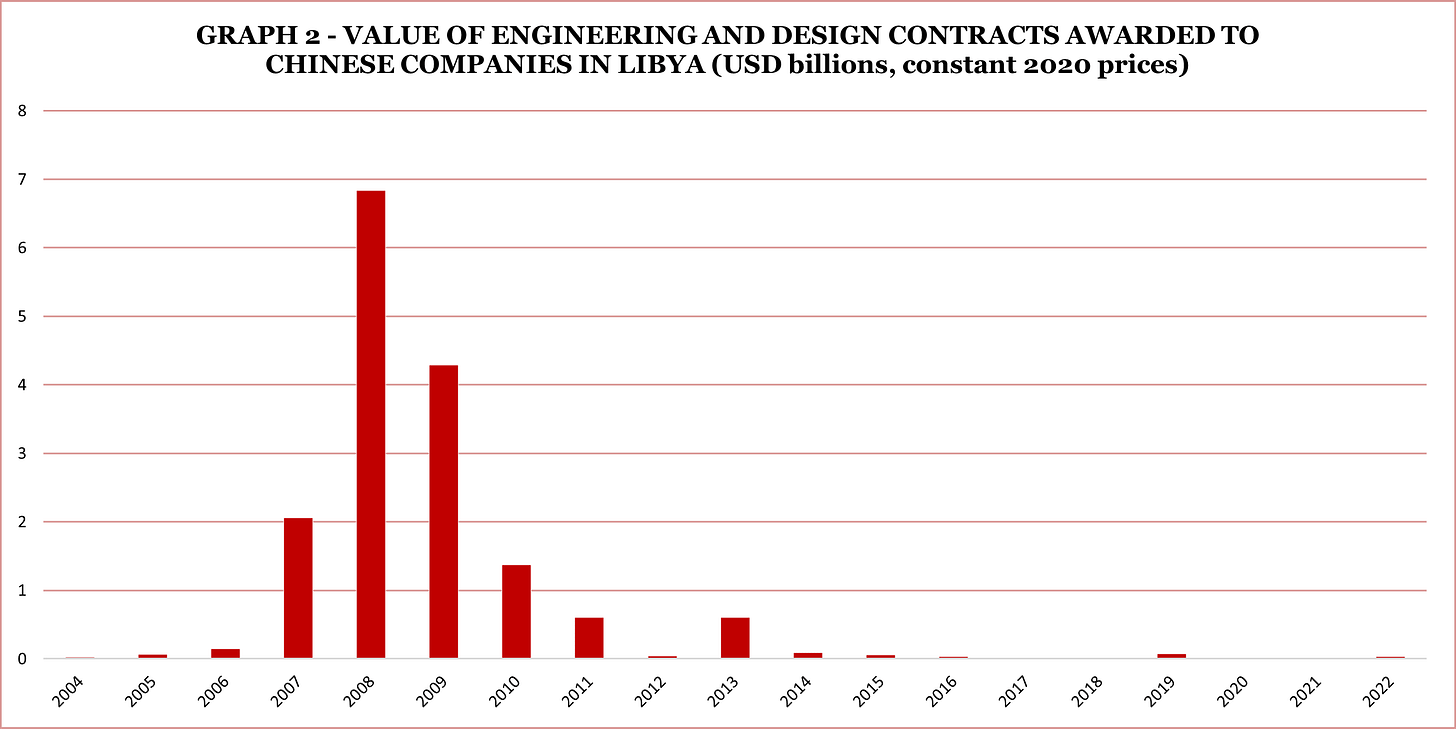

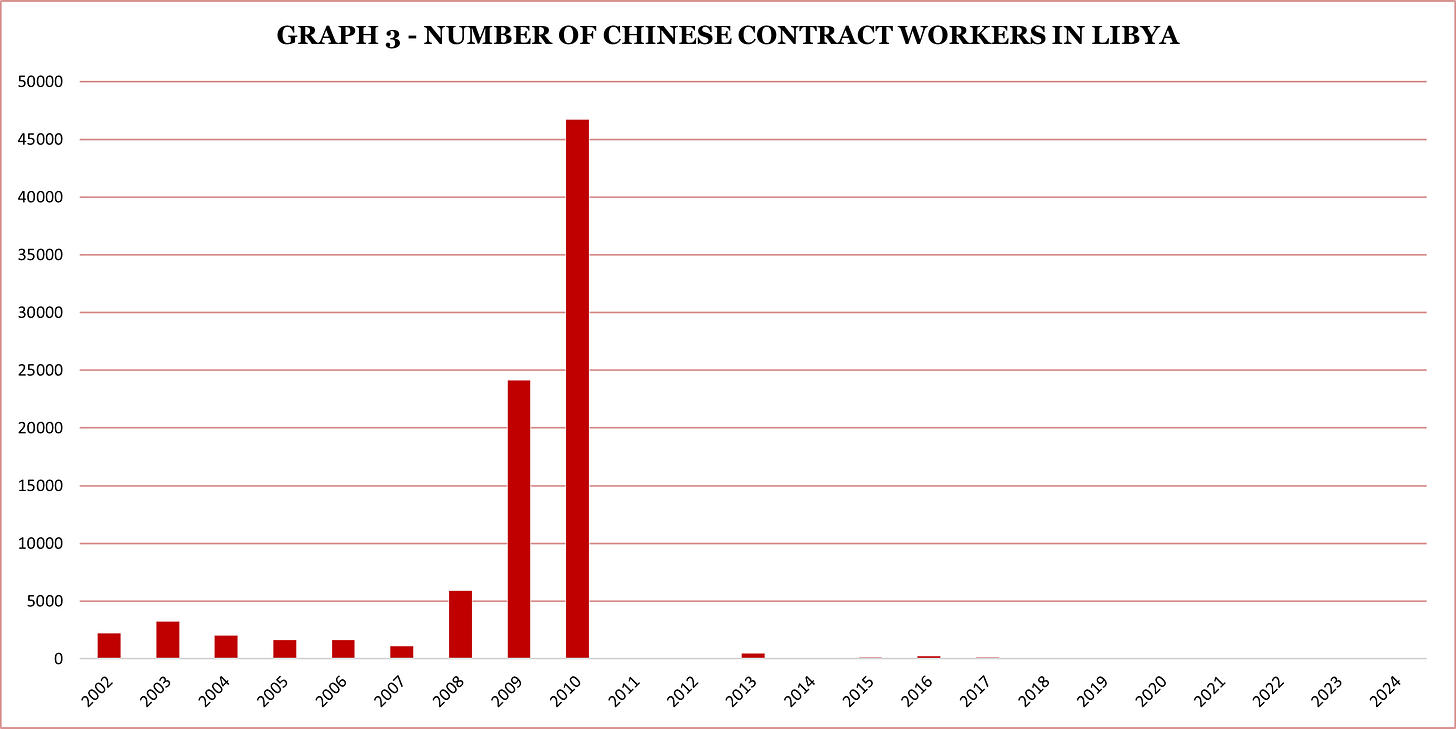

Before the conflict, Beijing was a major importer of Libyan oil (see graph 1), and Chinese state-owned enterprises were deeply involved in construction, energy, and infrastructure projects nationwide (see graph 2). However, an unintended risk of this mutually profitable partnership was that tens of thousands of Chinese nationals were on Libyan soil when war broke out (see graph 3). Their safety was an immediate concern for Beijing, which mounted an unprecedented response: in March 2011, China carried out its largest overseas evacuation, extracting more than 35,000 citizens from Libya, an active war zone thousands of kilometers from its borders.

China’s unprecedented response and ability to operate in the Mediterranean caught many European observers off guard (this episode spurred the creation of the ChinaMed Project later that same year). At the same time, the operation’s reliance on chartered civilian ships and aircraft laid bare the limits of China’s power-projection capabilities. As such, experts regard the Libya evacuation as having catalyzed Beijing’s subsequent push to modernize its military, establish its first overseas base in Djibouti, and refine its doctrine for “military operations other than war.”[6]

Analysts like Jesse Marks also see Libya as the watershed moment in China’s approach to conflict resolution in the region. In March 2011, as violence spiraled out of control, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1973 that sanctioned the NATO-led intervention by authorizing a no-fly zone and “all necessary measures” to protect civilians. Despite its veto power and commitment to non-interference, China chose to abstain to avoid alienating the Arab League and the African Union which supported the resolution.[7]

By ultimately toppling Gaddafi’s regime, however, the intervention contributed to plunging the country into prolonged political instability and a severe humanitarian crisis. In the aftermath, Beijing adopted a more skeptical posture toward Western-led interventions, doubling down on the primacy of state sovereignty and negotiated settlements.

This shift was most evident regarding Syria, where China repeatedly vetoed UN Security Council resolutions it believed could open the door to regime change. At the same time, China further prioritized cultivating ties with key regional actors and expanding its multilateral frameworks in the region not merely to insulate its relationships from future diplomatic divergences, but also to shape the contours of the regional debate itself.[8]

Although China abstained from Resolution 1973, it was quick to criticize NATO airstrikes. This somewhat discongruous posture allowed Beijing to pursue what Sandy Alkoutami and Frederic Wehrey described as a strategy of “cautious” and “calculated” neutrality during the 2011 Libya war. In practice, China hedged its bets: preserving ties with Gaddafi’s collapsing regime while opening channels to the opposition National Transitional Council (NTC), which Beijing formally recognized as Libya’s sole legitimate authority in September 2011, following the fall of the capital Tripoli.[9]

This ambiguity initially led to mistrust. At first, the NTC viewed Beijing warily amid accusations that China had sought to skirt the arms embargo to supply Gaddafi. However, through sustained diplomatic outreach after the war, China managed to repair relations with Libya’s post-Gaddafi leadership. As Alkoutami and Wehrey note, these efforts not only helped restore China’s prewar economic footprint but also left Beijing in relatively good standing with successive UN-recognized, Tripoli-based governments.[10]

Those governments, for their part, proved incapable of unifying the anti-Gaddafi camp. Rival factions hardened, Islamist groups expanded their reach, and state authority steadily fragmented. Against this backdrop, Khalifa Haftar and his LNA launched Operation Dignity in eastern Libya in May 2014, ostensibly to eliminate Islamist militias, but widely perceived as a bid for dominance. In response, opposing Islamist militants and armed groups coalesced into the Libya Dawn coalition, leading to fighting erupting around Tripoli and across the east, plunging Libya into its second civil war.

Heavy foreign intervention quickly followed, unsurprising given the strategic prize of Libya’s vast oil reserves. Broadly speaking, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, France, and Russia supported the LNA, while Türkiye, Qatar, and Italy backed the UN-recognized authorities in Tripoli. These states did not merely act through proxies; several intervened directly, deploying airpower, military advisers, and mercenaries. Türkiye’s role was especially consequential, tipping the balance against Haftar’s 2019 surprise offensive on Tripoli.

A UN-brokered ceasefire in October 2020 briefly raised hopes for national reconciliation and elections. Those hopes have since faded, with any progress stalling amid disputes over electoral rules and candidate eligibility. The east-west divide between the GNU and LNA has only become more entrenched, with periodic and often intense clashes continuing to punctuate this uneasy stalemate.

Throughout this second civil war and its unresolved aftermath, Beijing has largely maintained its posture of neutrality and balancing. As in conflicts such as Yemen, China has consistently called for a political solution that preserves Libya’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, while condemning foreign interference.

Yet, for much of the past decade, many analysts have questioned if this neutrality has ever been truly even-handed. Samuel Ramani has argued that China tilted toward Tripoli-based governments over Haftar-aligned authorities in the east. This tendency is consistent with Beijing’s longstanding preference for UN-recognized governments and is reflected in its sustained (though not exclusive) diplomatic engagement with the GNU and its predecessors.[11]

Jalel Harchaoui argued that this preference is also motivated by economic concerns, (this reflects a broader tendency to view China’s Libya policy as “economy first” by default). Tripoli-based authorities control the highly contested Central Bank of Libya, the sole legal repository of the country’s oil revenues, granting the GNU the unique ability to disburse funds, sign contracts, and allocate capital. When Chinese state-owned PetroChina signed an annual contract with Libya’s National Oil Corporation in May 2018, it necessarily relied on, and reinforced, the financial primacy of Tripoli.[12]

Nor has the relationship been one-sided. Tripoli, for its part, has actively courted Chinese investments by joining the BRI in 2018.[13] Since then, successive Tripoli-based governments have sought to market Libya as a destination for Chinese capital, not only in hydrocarbons, but also in infrastructure and telecommunications, pointing to firms such as Huawei and ZTE as possible partners. This outreach has continued under the current government. In June 2024, at the inaugural Chinese-Libyan Economic Forum in Beijing, GNU Prime Minister Abdulhamid al-Dbeibah urged Chinese companies to restart suspended projects, explicitly casting Beijing as a central actor in Libya’s reconstruction.

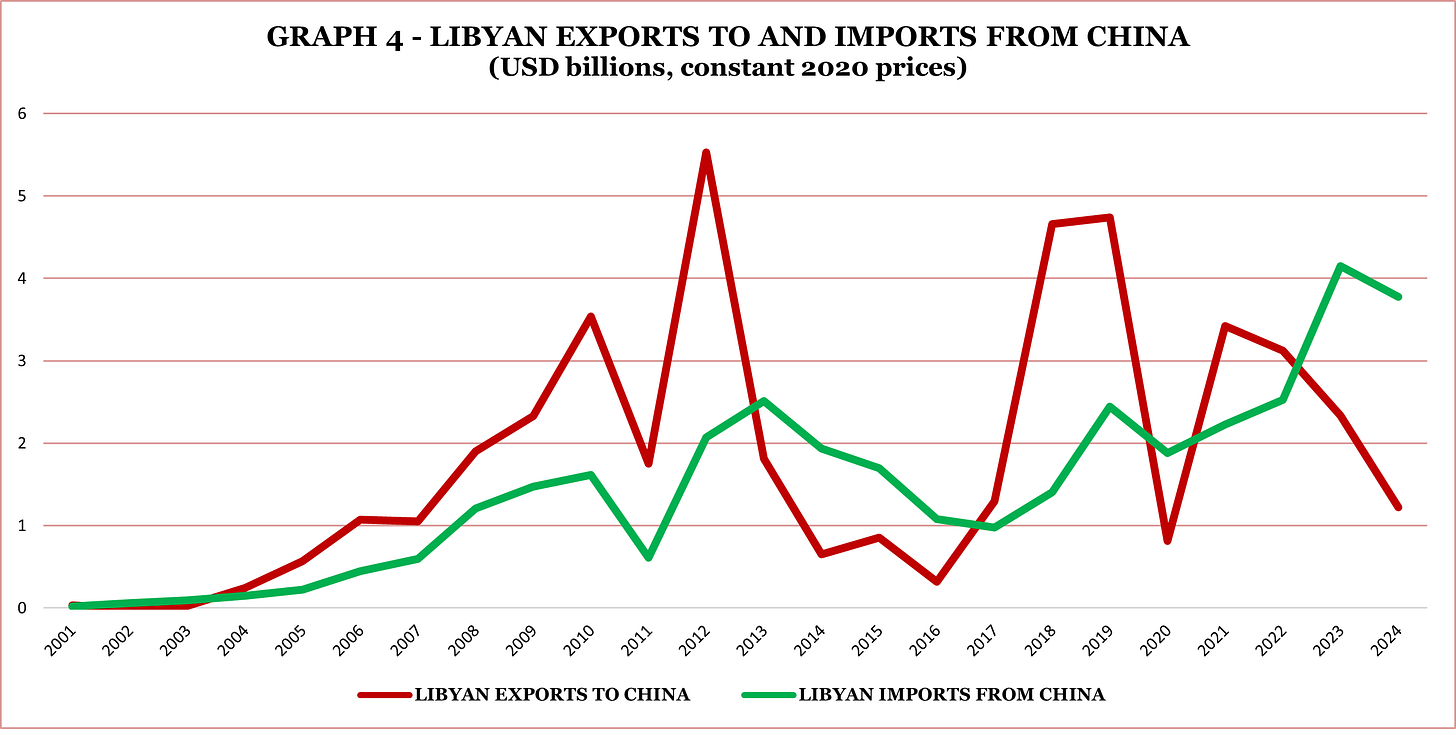

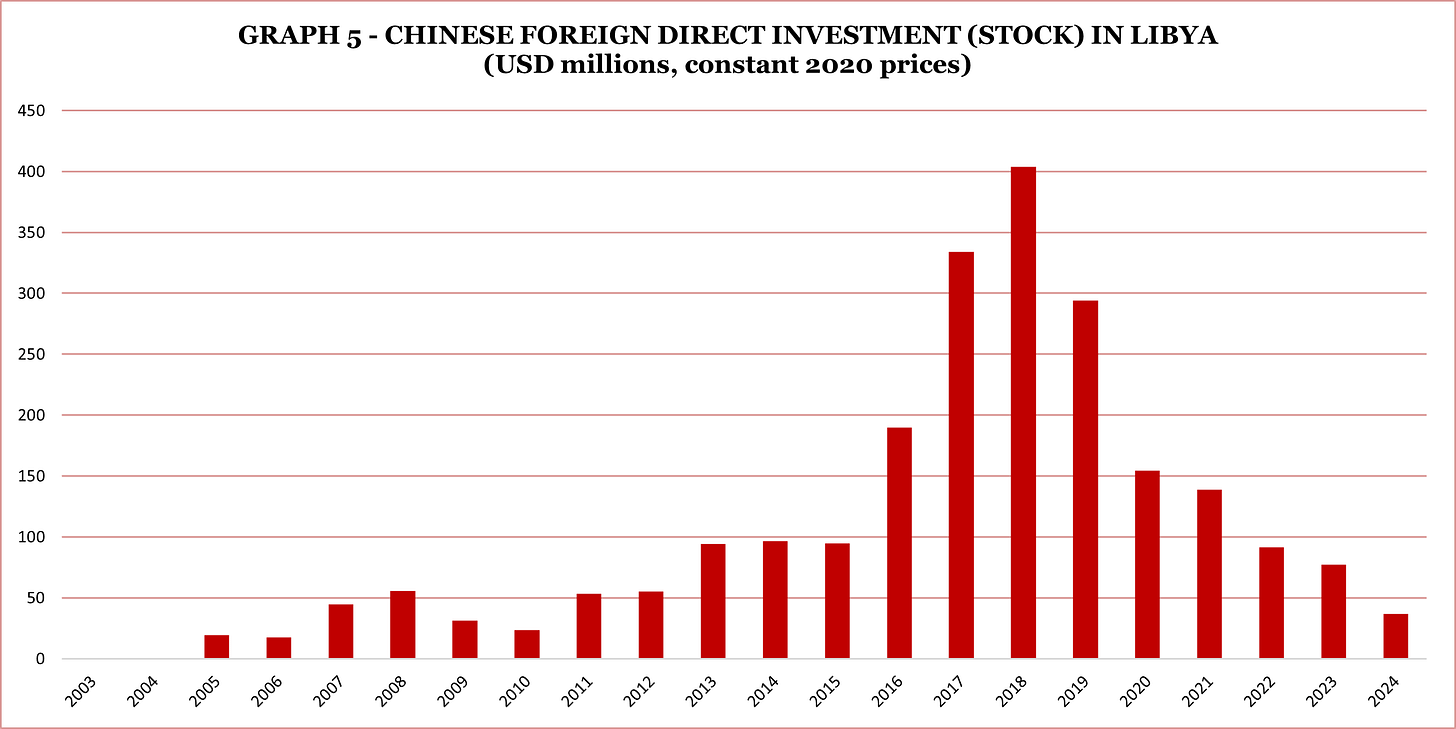

China’s response has been cautious but noteworthy. Bilateral trade has grown over the last few years and Chinese firms have signed on to restart frozen infrastructure projects (see graphs 4 and 5). The November 2023 memorandum of understanding between the Misrata Free Zone and China Harbour exemplifies growing Chinese interest in investing in GNU-controlled territory.

However, this deepening economic and diplomatic relationship has clear limits. Even as Beijing elevated ties with Tripoli to a “strategic partnership” during the visit to China of the (GNU-linked) Libyan Presidency Council head Mohammad al-Manfi, it has stopped short of translating the relationship into tangible security support – something Tripoli has sought. As Harchaoui noted, Beijing has declined Tripoli’s requests to help lift the UN arms embargo or to assist it in accessing Libya’s frozen sovereign wealth fund.[14]

This restraint speaks to both China’s reluctance to become entangled in Libya’s security quagmire and its determination not to foreclose options in the east. Beijing has consistently kept open channels with Haftar, hedging against the uncertain trajectory of the Libyan conflict and likely mindful that much of Libya’s oil infrastructure lies in LNA-controlled territory. At the same time, recent developments have led to speculation that China may be leaning toward a more active role in Libya’s security landscape, and perhaps even beginning to tilt, cautiously, toward the LNA.

For years, analysts have argued that, from Beijing’s perspective, it mattered little who ultimately “won” in Libya. China’s priority, the argument went, was to keep open channels to all plausible power centers, ensuring a seat at the table when postwar reconstruction began.[15]

China’s hedge, however, may no longer be evenly balanced. A growing body of reporting suggests that China’s interest in Libya may be drifting eastward, away from the GNU and toward Haftar. Where Chinese firms once avoided acknowledging interest in the east, now the picture looks markedly different. Reports of Chinese interest in the Haftar-controlled Benghazi airport, the ports of Tobruk and Sirte, and long-discussed railway links connecting Cyrenaica to the Sahel now circulate with increasing frequency, often framed within the BRI.[16]

However, these projects’ feasibility and the depth of Chinese financial commitment remain an open question. Much of the apparent uptick may simply reflect improving operating conditions in the east, particularly following the establishment of the Energy and Mining Bank, intended to provide eastern authorities greater financial autonomy and contracting capacity. Even if the headline projects remain aspirational, Chinese firms appear sufficiently active in the east to have provoked a reaction from Tripoli: the GNU has suspended Huawei’s operations in western Libya, citing the company’s role in developing telecommunications infrastructure in LNA-controlled areas.

Economic engagement with multiple sides is hardly unusual for China, and, on its own, would not signal a strategic realignment. What has truly fueled speculation are several high-profile, security-related episodes that hint, however ambiguously, at a more direct role.

In June 2024, Italian customs authorities intercepted two Chinese-made military drones at the port of Gioia Tauro. Shipped from Yantian and bound for Haftar-controlled Benghazi, the cargo was concealed as wind turbine components, an apparent attempt to circumvent the UN arms embargo on Libya.

More troubling still was an investigation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which alleged that China-linked firms had plotted to supply the LNA with up to US$1 billion worth of drones, disguised as COVID-19 humanitarian assistance. Shell companies were allegedly used to mask state involvement, with the investigation suggesting the possible deliberate involvement of Chinese state-owned defense firms and even elements of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[17]

Investigators went further, suggesting that Beijing’s underlying logic may have been “using war to end war quickly” by tipping the balance in Haftar’s favor.[18] That conclusion, however, remains contested. Ghiselli, for example, has cautioned against reading the episode as evidence of a centrally directed Chinese strategy, noting that even large Chinese state-owned enterprises have at times acted with considerable autonomy, often to Beijing’s irritation.[19]

Moreover, Chinese-made drones have been present in Libya for more than a decade, most prominently the Wing Loong systems deployed by the LNA as early as 2016. Those drones were procured and operated by the UAE, not China, with Beijing insisting that such sales were purely commercial transactions unrelated to its political stance on Libya. Even Western officials have largely concurred. In 2020, Wolfgang Pusztai, former Austrian defense attaché to Libya and chairman of the advisory board of the National Council on U.S.-Libya Relations, noted that there was no evidence China had directly supplied weapons to either side.[20] Chinese drones, after all, are ubiquitous across the region and can just as easily be found trained on one another in the arsenals of rival states such as Algeria and Morocco.

More recent developments, however, have further muddied the waters. Last month, Pakistan reportedly finalized a US$4 billion deal to supply the LNA with military equipment over the next two and a half years, including sixteen JF-17 “Thunder” fighter jets. The fourth-generation fighter is jointly developed by China’s Chengdu Aircraft Corporation and the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex, a fact that has drawn attention to Beijing’s possible role. However, the driving force behind this deal appears to be Pakistani, not Chinese.[21]

Islamabad has aggressively marketed the JF-17 as a cost-effective, combat-tested alternative to Western aircraft following its reportedly successful deployment during recent clashes with India.[22] This push is both recent and potentially overextended, and may amount more to marketing than sustainable export capacity. Libya remains subject to a UN arms embargo – frequently violated, but still consequential – and analysts have questioned if Pakistan has the industrial and logistical capacity to honor a growing slate of large, long-term, and in some cases unconfirmed defense agreements, most notably an alleged deal with Saudi Arabia.[23] These uncertainties cast doubt on whether fulfilling a contract with the non-UN-recognized authorities in eastern Libya would rank as a strategic priority for Pakistan, let alone for China.

Amid this landscape of ambiguous commercial ties and third-party arms transfers, Beijing’s clearest move has come not on the battlefield or in the boardroom, but in the diplomatic sphere. After much delay, China has relocated its embassy staff from Tunis back to Tripoli. Far from signaling support for the LNA, a rival authority that has repeatedly sought to seize the Libyan capital by force, this move points to a measure of confidence in the GNU and a desire to further strengthen ties with the UN-recognized government. More plausibly still, it reflects a pragmatic need to monitor developments more closely on the ground, as Libya, and the wider region, enter a period of recalibration shaped by the end of the war in Syria and an emerging rift pitting the UAE and Israel against Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Türkiye.

In the immediate aftermath of the Assad regime’s collapse in Syria to rebel forces, a wave of reporting suggested that Russia was rapidly redeploying military and naval assets from the Syrian port of Latakia to LNA-controlled territory in Libya.[24] Since then, Tobruk and the base in Maaten al-Sarra have been cast by analysts as the new logistical gateways for the Africa Corps – the rebranded successor to the Wagner Group – supporting Russian operations across sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Sahel.

Beyond Russian maneuvers, another decisive dynamic reshaping Libya is the widening rift between the once close partners of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Abu Dhabi’s normalization with Israel under the Abraham Accords, and its continued engagement with Tel Aviv amid the Gaza war, has increasingly set it apart from Riyadh and other Gulf capitals, particularly after Israel’s escalatory military actions against Syria’s new regime, Iran and Qatar.

Simmering tensions over Sudan, Somalia and Yemen finally boiled over in December 2025. In Yemen, the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council launched an offensive against the Saudi-backed internationally-recognized government. Riyadh responded with a direct military intervention, decisively routing the southern forces and laying bare the depth of the Gulf rupture.

Libya is deeply enmeshed in this broader fracture. The UAE remains one of the LNA’s main external backers, with Haftar serving as a critical nexus in a wider Emirati-backed network that includes Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces, now locked in a brutal civil war against the Sudanese Armed Forces, who in turn, are backed by Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Türkiye. As Emirati assertiveness grows, Cairo, Riyadh and Ankara have increasingly coordinated their stances on regional files. Should this alignment deepen, the once-cohesive external coalition supporting the LNA could begin to unravel if Egypt and Saudi Arabia draw closer to Türkiye, Tripoli’s most influential military patron.

Recent developments in Syria and Yemen have also delivered a hard lesson for Haftar: his key backers, Russia and the UAE, are far from infallible guarantors. Still, this does not necessarily spell the end of the LNA. While Haftar is now eighty-two, he has already cultivated a successor in his son Saddam Haftar, who has embarked on an international tour stopping in Paris and Cairo. Moreover, the LNA’s firm grip over eastern Libya, both territorially and militarily, sharply contrasts with the west, where the GNU remains hollowed out by corruption and fragmented authority, hostage to militias and local power brokers.

Adding further complexity is the Mediterranean dimension. Amid concerns over migration flows and volatile energy prices, Libya retains strategic importance for Italy, France, and Greece. However, European involvement has been anything but straightforward. The rival ambitions of Rome and Paris, each backing opposing factions or trying to outmaneuver the other as peace broker, have undermined any hope of a unified EU strategy on Libya.

China and Russia’s entrenched presence in the country has only heightened Italian and European unease. Though the Syrian case cautions against assuming seamless Sino-Russian alignment in Libya, the revival of power-politics thinking in Europe has fueled skepticism toward China’s role. This skepticism is especially pronounced in Italy, where commentators, policymakers and military voices view the former Italian colony as within Rome’s “natural” sphere of influence, vital to energy security, migration management, and national security.[25] This is despite Chinese diplomats having in the past indicated openness to cooperate with Italy on Libya, likely motivated by a shared preference for Tripoli over Benghazi.[26]

In such a crowded and complex environment, which recently saw the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) extend its mandate in hopes of advancing the UN roadmap, it is unsurprising that Chinese officials have sought a more visible on-the-ground presence by reopening their embassy – a move which, however, should not be mistaken for deep commitment.

As Libya and the wider region enter a period of recalibration shaped by the end of the war in Syria and the emerging rift between the UAE and Israel against Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Türkiye, the return of Chinese diplomats to Tripoli reflects Beijing’s pragmatic need to monitor developments more closely on the ground while maintaining a position of cautious and calculated neutrality between the Libyan factions.

While Chinese defense companies have seemingly participated in Libya’s security landscape through third parties, it remains highly unlikely that China would seek a direct role in the conflict. The most plausible explanation is that Beijing tolerated some security-related engagement with the LNA as a way to maintain relations with the most significant stakeholder in eastern Libya. The LNA’s relative cohesion, compared to the fractured and internally weak GNU, might also position Haftar as a key player should a long-anticipated power-sharing agreement materialize.

The Syrian experience likely informs this cautious approach. China’s steadfast support for the UN-recognized government of Bashar al-Assad ultimately left it exposed when his regime collapsed, temporarily locking Beijing out of engagement with the new Syrian authorities and undermining Chinese interests, particularly regarding Uyghur fighters operating in the country.

Any Chinese engagement with the LNA, then, is best understood not as a pivot but as insurance: a way to remain relevant without becoming entangled. As Libya remains only more crowded with external actors as Syria ever was, Beijing’s most rational course is to remain present, visible, and determined above all to keep its options open.

Bianca PASQUIER is a Project Officer and Research Fellow at the ChinaMed Project. She is also a graduate student in International Sciences at the University of Turin and holds a B.A. in Political Science and International Relations from the University of Naples “L’Orientale.” Her research interests include the foreign policies of MENA countries and the media coverage of China in North Africa.

Leonardo BRUNI is the Project Manager of the ChinaMed Project. He is also a Doctoral Researcher in History at the European University Institute, a Junior Research Fellow at the Torino World Affairs Institute (T.wai), and a graduate of the Sciences Po–Peking University Dual Master’s Degree in International Relations. His research interests include China-EU relations, the history of Sino-European relations, and Chinese foreign policy in the wider Mediterranean region.

[1] The authors would like to thank Davide Donald for his help and clarifications.

[2] Sami Zapitia, “Chinese Embassy officially resumes its operations from Tripoli today – after a 10-year closure due to security situation,” Libya Herald, November 12, 2025, https://libyaherald.com/2025/11/chinese-embassy-officially-resumes-its-operations-from-tripoli-today-after-a-10-year-closure-due-to-security-situation/;

The Libya Observer, “Chinese Embassy returns to Tripoli” November 14, 2025, https://libyaobserver.ly/index.php/inbrief/chinese-embassy-returns-tripoli.

[3] Agenzia Nova, “China to reopen its embassy in Tripoli in November,” October 31, 2025, https://www.agenzianova.com/en/news/la-cina-riaprira-la-propria-ambasciata-a-tripoli-a-novembre/.

[4] Formiche is an Italian political and strategic affairs magazine. Rather than a mass-circulation news outlet, it is more a platform for analytical commentary and agenda-setting aimed at policymakers, civil servants, diplomats, and business leaders. It has an Atlantist editorial line.

[5] Emmanuele Rossi, “Cosa racconta il ritorno della Cina in Libia” [What China’s Return to Libya Tells us], Formiche, December 13, 2025, https://formiche.net/2025/12/cosa-racconta-il-ritorno-della-cina-in-libia/ (a partial translation in English is also available on Decode39, a spin-off project of Formiche).

[6] See Andrea Ghiselli, “Diverse Threats, Diverse Responses,” Protecting China’s Interests Overseas: Securitization and Foreign Policy (Oxford, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198867395.003.0007;

Carine Pina, “La Chine et les opérations militaires autres que la guerre (军队非战争军事行动) à l’étranger : quelles conséquences sur le dilemme de sécurité ?” IRSEM n°115, March 2025, https://www.irsem.fr/actualites/etude-de-l-irsem-n-115-2024.html

[7] Jesse Marks, “The Legacy of Libya in Chinese Foreign Policy,” Coffee in the Desert [Substack], December 29, 2024, https://jessemarks.substack.com/p/the-legacy-of-libya-in-chinese-foreign.

[8] Jesse Marks, “China’s evolving conflict mediation in the Middle East,” Middle East Institute, March 25, 2022, https://mei.edu/publication/chinas-evolving-conflict-mediation-middle-east/.

[9] Sandy Alkoutami and Frederic Wehrey, “China’s Balancing Act in Libya,” Lawfare, May 10, 2020, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/chinas-balancing-act-libya.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Samuel Ramani, “Where Does China Stand on the Libya Conflict?,” The Diplomat, June 18, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/06/where-does-china-stand-on-the-libya-conflict/.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Later that same year, in December 2018, Libya also joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. https://libyaobserver.ly/index.php/inbrief/libya-joins-china-based-aaib.

[14] Guy Burton, “Will China Become More Active in Libya?,” The Diplomat, February 19, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/will-china-become-more-active-in-libya/.

[15] Giorgio Cafiero, “The Geopolitics of China’s Libya Foreign Policy,” ChinaMed Project, August 4, 2020, https://www.chinamed.it/publications/the-geopolitics-of-chinas-libya-foreign-policy.

[16] Al-Estiklal, “China Leverages Economic Ties to Win Over Both Sides in Libya: How?,” September 9, 2025, https://alestiklal.net/en/article/china-leverages-economic-ties-to-win-over-both-sides-in-libya-how;

Sage, “China’s Expanding Strategic Footprint in Libya: Energy, Infrastructure, and a New Gateway to Europe,” SinoSage [Substack], July 3, 2025, https://sinosage.substack.com/p/chinas-expanding-strategic-footprint.

[17] Sophia Yan, “Inside China’s secret plan to send weapons disguised as Covid aid to warlord,” The Telegraph, December 26, 2024, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2024/12/26/chinas-secret-plan-to-send-armed-drones-to-libyan-warlord/.

[18] Tom Kington, “Chinese COVID aid talks with Libyans called a plot to smuggle drones,” Defense News, September 27, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2024/09/27/chinese-covid-aid-to-libya-is-labeled-a-plot-for-smuggling-war-drones/.

[19] Emanuele Rossi, “Cina in Libia? Che cosa raccontano i droni in cambio di petrolio” [China in Libya? What do the drones exchanged for oil deal tell us], Formiche, December 31, 2024, https://formiche.net/2024/12/cina-in-libia-che-cosa-raccontano-i-droni-in-cambio-di-petrolio/.

[20] See note 15, Giorgio Cafiero, ChinaMed Project, August 4, 2020, https://www.chinamed.it/publications/the-geopolitics-of-chinas-libya-foreign-policy.

[21] MEE staff, Pakistan seals $4bn arms deal to sell Chinese warplanes to Libya’s Khalifa Haftar: Report,” Middle East Eye, December 22, 2025, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/pakistan-seals-4bn-arms-deal-sell-chinese-warplanes-libyas-khalifa-haftar-report.

[22] Zia Ur Rehman, “Why Pakistan’s war with India led to a boom in arms sales and defence ties,” Middle East Eye, January 16, 2026, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/why-pakistans-war-india-led-boon-arms-sales-and-defence-ties.

[23] Snehesh Alex Philip, “The curious case of Pakistan’s JF-17 ‘orders,’” The Print, January 15, 2026, https://theprint.in/the-fineprint/the-curious-case-of-pakistans-jf-17-orders/2827270/.

[24] Leela Jacinto, “Fallout of Assad’s ouster in Syria ripples down the Mediterranean to Libya,” France24, December 20, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20241220-fallout-assad-ouster-syria-ripples-down-mediterranean-libya.

[25] Jacopo Marzano, “La forza della penetrazione tecnologica cinese nel dietrofront su Huawei in Libia” [The strength of Chinese technological penetration in the about-face on Huawei in Libya], Formiche, August 28, 2025, https://formiche.net/2025/08/la-forza-della-penetrazione-tecnologica-cinese-nel-dietrofront-su-huawei-in-libia/;

Federico Di Bisceglie, “L’Italia oggi conta di più in Europa, ora una proiezione mediterranea. La versione di Quagliariello” [Italy today counts more in Europe, now to project in the Mediterranean. Quagliariello’s view], Formiche, December 27, 2025, https://formiche.net/2025/12/litalia-oggi-conta-di-piu-in-europa-ora-una-proiezione-mediterranea-guidata-dal-piano-mattei-parla-quagliariello/;

Fabio Caffio, “La Cina nel Mediterraneo, uno scenario possibile raccontato dall’amm. Caffio” [China in the Mediterranean: A Possible Scenario, as Told by Admiral Caffio], Formiche, December 9, 2025, https://formiche.net/2025/12/la-cina-nel-mediterraneo-uno-scenario-possibile-raccontato-dallamm-caffio/.

[26] Guido Santevecchi, «Cina e Italia insieme in Libia per fermare i profughi e battere il terrorismo» [“China and Italt together in Libya to stop the refugees and to defeat terrorism”], Corriere della Sera, January 22, 2008, https://www.corriere.it/esteri/22_gennaio_08/cina-italia-insieme-libia-fermare-profughi-battere-terrorismo-189c9bfc-70ae-11ec-bed9-868e21cce827.shtml.